Timelines, time, lines.

Lines that allude to a time between, a time before, a time to come.

Lines are ever present,

and tellers of time.

Timelines, time, lines.

Lines that allude to a time between, a time before, a time to come.

Lines are ever present,

and tellers of time.

A figurative visualisation, reflecting my own memories of the Antarctic landscape combined with elements pivotal to Jo’s field expeditions and geochemical research.

A small envelope holding something precious arrived for me this week! It contained this tiny but very significant piece of Basalt rock retrieved from World’s End Bluff in West Antarctica.

The sliver of stone is a remnant from one of Jo’s valuable geology samples, which she collected herself during the 2019 field season for the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration.

This photo shows the remoteness of World’s End Bluff, a Nunatak in a sea of ice amid the Hudson Mountains - just wow! There is no doubt that undertaking work in such extreme environments takes a special commitment, determination and resilience. I have great respect for all those involved.

I’m excited at the possibilities for using this authentic basalt specimen in my artwork in a metaphorical way. I am hugely grateful for the chance to include it. Diminutive yes but it bears enormous relevance all the same!

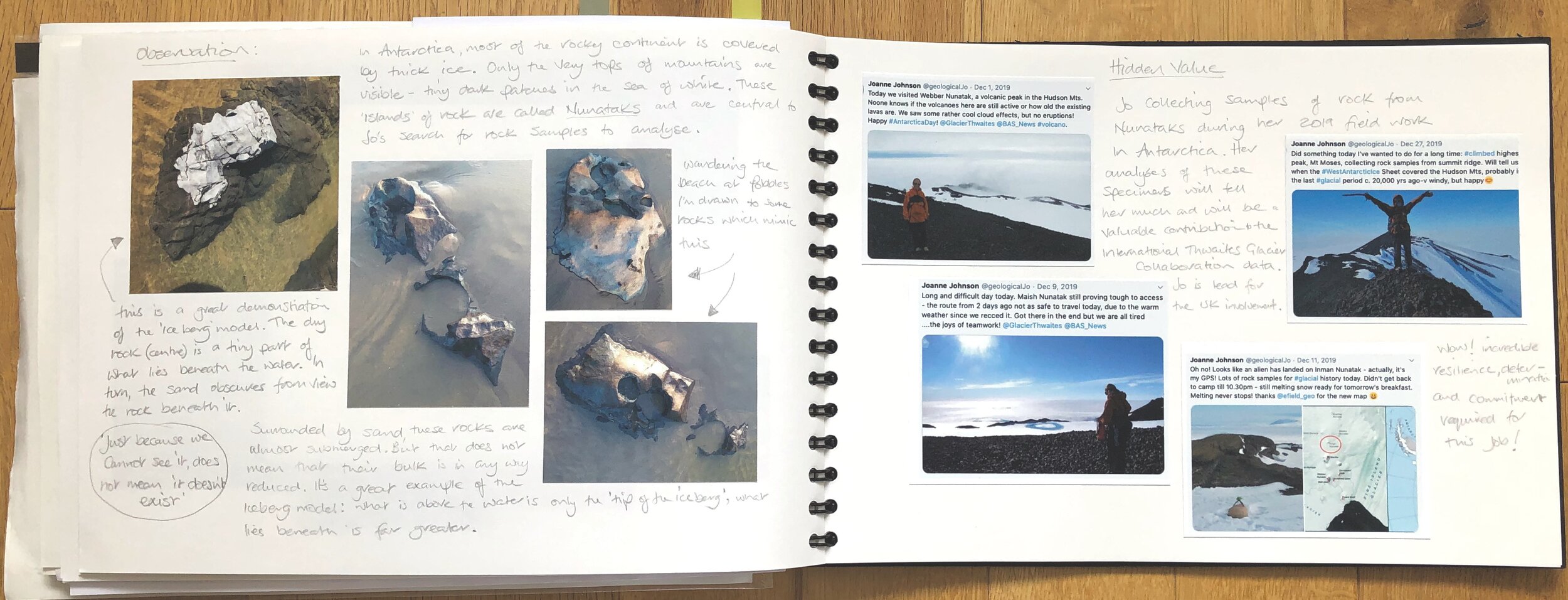

Nunataks are the very tops of mountains which poke through vast fields of inland snow and ice and are otherwise completely engulfed. This page from my notebook details my observations from a walk on the beach which demonstrate the concept of nunataks brilliantly - but on a tiny scale, with sand and sea instead of snow and ice. It’s the same principle!

Exploring physical chemistry through paint: using colour and movement to envisage reactionary processes which take place at an atomic level. They form key components central to Jo’s analytical work.

Evidence still exists of reactions that occurred hundreds, often thousands of years ago within the Antarctic rock sought for analysis by Jo. I find that astonishing.

Surrounded by craggy cliffs at Pobbles bay it’s easy to become absorbed in the visual appeal of such a place. But I’m also excited by what I can’t see; the phenomenal wealth of information locked away inside the rocks. Ever present yet hidden, the material within speaks of so much. The world’s geological record is an actual account of earth’s evolution and provides an extensive library there for the reading. It yields a huge knowledge base of physical and chemical happenings which can be examined, assessed, counted and calculated. Its reading and analysis involves disciplines across the scientific spectrum and, with the rapid advancement of scientific knowledge and research, unlocking our past is now helping us with predicting the future. I find this utterly amazing! It is incredible that today, by joining forces and collaborating, climate scientists like Jo from all over the world can piece together intricate pictures of what happened previously, when, where, why and by how much. By utilising our increasing technological capabilities and continuing to access our geological record we are expanding exponentially and in ground breaking ways, our understanding of what was and of what might be. The more we uncover the more we seek to uncover; the more we learn, the more we can learn. It’s a truly fascinating, self-perpetuating circle of enlightenment that is of tremendous value to us all - even if some of us don’t know it.

This provides me with huge scope for my creative explorations of the relationship between absence and presence. It enables me to examine and to challenge, in a multitude of ways, their perceived hierarchical ranking. Much to do with Jo’s work goes unseen by the naked eye yet is of prodigious significance and has global relevance. As a geochemist with British Antarctic Survey she works at the forefront of international climate science, making an invaluable contribution to the research around potential sea level rise. Jo looks for, retrieves, analyses, assimilates, translates and presents information found in her geological specimens. Sometimes these are samples from rock which is itself hidden, like those from the bedrock concealed beneath vast West Antarctic ice sheets. Jo’s work is a true example of the immense importance of ‘the invisible in the visual’ (J F Lyotard).

Like pages in a book, these layers of sedimentary rock at Pobbles tell incredible stories. Of dynamic creation and evolutionary change, chemistry, biology, physics and geography, the evidence is there, preserved in stone.